Many of us feel a deep-seated fear of snakes, largely due to the widespread myth that they’re all venomous and their bites are inevitably deadly.

Yet, in reality, most snakes are non-venomous and wouldn’t harm us unless threatened. Sadly, because of these misunderstandings, many of us react impulsively, killing snakes on sight.

This has led to a noticeable decrease in their numbers, especially in semi-wooded areas close to our homes. We should remember that snakes often do us a favor by controlling rodent populations.

My List of The Top 10 Non-Venomous Snakes

10. My Encounter with The Northern Water Snake

During one of my trips across the United States, I came across this intriguing snake, aptly named for its preference for watery habitats like lakes, ponds, and marshes. Its resemblance to the venomous rattlesnake often leads to unfortunate misunderstandings, causing many to mistakenly harm or kill it.

While it’s true that the Northern Water Snake can be quite feisty and isn’t shy about biting, its bite is harmless, causing just a slight itch. I’ve also noticed, much like the Eastern Garter Snake, that it emits a distinct, unpleasant odor as a defense mechanism against threats. It’s quite a sight to see groups of them soaking up the sun together.

- If you want to read more articles on Snakes check here.

9. The Talk of Europe: The Four-Lined Snake

I’ve heard tales about a striking snake that graces the European landscapes, known as the Four-Lined Snake. It’s renowned as Europe’s largest non-venomous rat snake. What sets it apart are the four vertical stripes that adorn its body, which can be shades of yellow or brown.

These lines not only give it a unique look but also make it one of the most visually appealing snakes globally. Growing impressively long, some can stretch up to 1.8 meters! They’re known to feast on rats, lizards, and other small creatures. If you’re wandering through Italy, Greece, or Slovenia, you might just be lucky enough to spot one of these beauties.

8. The Eastern Garter Snake

From what I’ve heard, the Eastern Garter Snake is a native of North America, often spotted in grasslands and deserts. It’s got a feisty spirit and won’t hesitate to strike if it feels cornered, even by humans. But there’s no need to panic; their bite is harmless.

A unique defense mechanism they employ is releasing a pungent odor from their glands, which usually deters any potential threats, buying them time to slither away. These snakes showcase a vibrant mix of yellow, green, black, and brown stripes and can grow up to an impressive 26 inches. Interestingly, they’re also known to hibernate, joining the ranks of animals that take long winter naps.

7. The Emerald Tree Boa

I’ve come across tales of the mesmerizing Emerald Tree Boa, often mistaken for the green python due to its striking resemblance in size, vibrant green hue, and white markings. Preferring the high life, these boas spend most of their time coiled around tree branches.

They’re part of the constrictor family and boast an impressive length of up to 2 meters. What’s fascinating is their long fangs, the longest among non-venomous snakes. But don’t be deceived; these fangs aren’t for venom injection. Instead, they rely on their robust body muscles and tail to navigate between branches. Many consider them among the world’s most beautiful snakes, and I can see why.

6. Tales of The Rough Green Snake

The Rough Green Snake, native to the United States, is aptly named for its vibrant green hue. Its back radiates a bright green while its belly transitions to a softer yellow, a clever camouflage for both arid and lush terrains.

Often referred to as the green grass snake, it thrives in open spaces with sparse trees. Its appearance is reminiscent of the green vine snake found in India, thanks to its elongated body and green shade.

These serpents can stretch up to 45 inches and have a diet consisting of insects, frogs, and lizards. There are also intriguing tales about apex predators worth exploring.

Interestingly, female Rough Green Snakes tend to be larger than their male counterparts. A distinctive feature of this species is its keeled dorsal scales and notably large eyes relative to its size. In the wild, they typically live up to 5 years, but some have been known to reach 8 years.

However, life isn’t always easy for them; they often fall prey to larger snakes like black racers or king snakes, birds, domestic cats, and even some spiders. This snake goes by various names, including green whip snake, green summer snake, green tree snake, huckleberry snake, and vine snake.

It’s worth noting that it’s sometimes confused with its American cousin, the smooth green snake, sharing names like grass snake or green grass snake.

5. Legends of The Bull Snake

The Bull Snake, a cousin to the Black Rat Snake, roams regions of the United States, Canada, and Mexico. Though not as lengthy, with its longest recorded size being 72 inches, it shares some behaviors with the Black Rat Snake. When cornered, it mimics the rattling of its tail and produces a hissing sound.

Adorned with contrasting dark and light brown patterns, it thrives in areas with sparse trees and farmlands.

By feasting on rodents, it inadvertently safeguards crops. Its menu primarily features rats, rabbits, and the occasional small bird. For those intrigued by nocturnal creatures, there’s a list of stunning animals that come alive at night.

A distinctive trait of the Bull Snake is its prominently keeled scales, lending a rough texture compared to other snakes. It also sports dark vertical lines between its upper lip scales, which stretch diagonally from its eyes to the back of its throat.

While its typical hue is a blend of ground color with reddish or brownish blotches from head to tail, there have been sightings of unique color variations, including white and albino. Come March, it’s breeding season for these snakes, and they lay their eggs between April and June.

Interestingly, the female lays a multitude of eggs but doesn’t guard them, allowing nature to take its course. When the young emerge, they display a grayish hue and measure between 20 to 46 cm.

4. The Black Rat Snake

The Black Rat Snake is a familiar sight in North America, standing out due to its impressive size. Often reaching lengths of up to 6 feet, it’s versatile in its choice of home, from rocky terrains to dense woods. An interesting defense mechanism they’ve adopted is vibrating their tail amidst leaves, producing a sound eerily similar to a rattlesnake, though they lack a rattling tail.

Their diet, rich in small creatures like lizards and rodents, inadvertently benefits farmers by keeping crop-damaging rats at bay. Its unique color variations also earn it a spot among the world’s most beautiful snakes.

When it comes to reproduction, the Black Rat Snake has a yearly mating ritual, akin to other snake species. Both genders emit a distinct scent, signaling readiness to mate.

Males, being quite the charmers, often mate with multiple females. After a three-month gestation, a female can give birth to a brood ranging from 3 to a staggering 80 snakes. While most snake offspring are left to fend for themselves, there are instances where the Black Rat Snake mother might nurture her young.

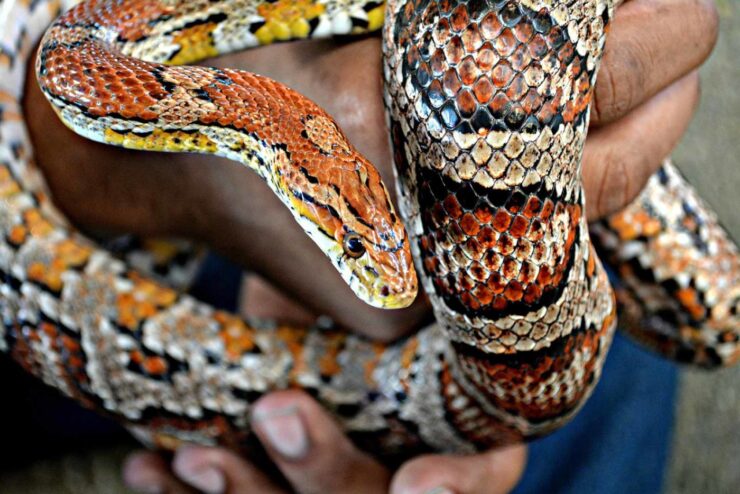

3. Mysteries of The Milk Snake

The Milk Snake, despite being non-venomous, often gets mistaken for the venomous Coral Snake due to its striking dark and light patterns. Its bands can range in hues from red to yellow or even orange, making it quite the eye-catcher. Native to North and Central America, particularly in mountainous terrains, its diet consists of earthworms, insects, and slugs.

While it might not match the size of some of its counterparts, its distinct appearance is undeniably captivating. For those with a penchant for strength, there are tales of the world’s mightiest animals worth exploring.

The intriguing name “Milk Snake” has led to some misconceptions. Contrary to popular belief, these snakes don’t have a penchant for milk. The moniker stems from old farmers’ tales, which claimed these snakes would sneak under cows to drink their milk.

However, science debunks this myth, pointing out that Milk Snakes don’t possess the anatomy to suckle from an udder. Size-wise, they vary considerably. The tiniest ones measure around 20 inches, while the giants can stretch up to 60 inches.

To put it in perspective, the largest Milk Snake can be three times the length of the smallest!

2. Legends of The Python

Often mentioned in the same breath as the anaconda, the python employs a similar hunting technique: constriction. By coiling its powerful body around its prey, it suffocates it. While not as massive as the anaconda, the python still ranks among the world’s most sizable snakes.

With 26 distinct species, pythons grace the landscapes of Asia and Africa, adapting to diverse habitats from wetlands and deserts to lush rainforests. Interestingly, they’re more prone to confront humans than anacondas.

Yet, many snake enthusiasts keep them as pets, with the ball python being a favorite choice. Their masterful camouflage not only aids in hunting but also in evading threats, earning them a spot among the world’s most visually stunning snakes.

When it comes to reproduction, female pythons are dedicated mothers. They lay between 12-36 eggs and vigilantly guard them, wrapping their bodies around the clutch to provide warmth. However, once the hatchlings emerge, maternal duties end, leaving the young to fend for themselves from day one.

Being ectothermic, these creatures bask in the sun to regulate their body temperature. Among the python family, the Reticulated Python stands out, boasting lengths of up to 30 feet. On average, a python’s weight hovers between 260-300 pounds, showcasing their impressive stature.

1. Myths and Realities of The Anaconda

Holding the title of the world’s largest snake, the Anaconda is both revered and feared. This non-venomous giant calls South America its home, with four distinct species under its name. The Green Anaconda stands out as the most massive, tipping the scales at 230 kilos and stretching up to 30 feet.

Employing a hunting technique of striking and then constricting its prey, the Anaconda is a master of suffocation. While they possess the might to harm humans, such incidents are rare.

Their appetite is vast, allowing them to tackle prey even larger than themselves, including wild pigs, caimans, and sizable fish. The Green Anaconda’s prowess earns it a spot among the formidable creatures of the Amazon rainforest.

Once its prey succumbs, the Anaconda consumes it whole. Being nocturnal, it primarily hunts under the cover of night. Mating season, typically in April and May, sees the female birthing 20-40 younglings after a six-month gestation.

These baby Anacondas, already 2 feet at birth, are self-sufficient from day one. It’s astounding to think they can consume up to 40 pounds of food daily. While there are four recognized Anaconda species, their immense size doesn’t make them easy to spot.

Even seasoned scientists find it challenging to locate them when they’re submerged in water, showcasing their elusive nature.

Adaptations for Prey Capture:

Non-venomous snakes have evolved a variety of methods to capture and consume their prey without the use of venom. One of the most notable adaptations is the ability of certain species to dislocate their jaws. This allows them to swallow prey that is significantly larger than their head.

Additionally, the backward-facing teeth of these snakes help grip the prey and prevent it from escaping as it’s swallowed whole. Some species, like the constrictors, coil around their prey, exerting pressure and causing suffocation. This method is highly effective and allows the snake to tackle prey of various sizes.

Mimicry:

Batesian mimicry is a fascinating evolutionary strategy where non-venomous snakes imitate the appearance of venomous ones to deter potential predators. This mimicry can be so convincing that even experienced herpetologists might have difficulty distinguishing between the two at first glance.

For example, the harmless Milk Snake bears a striking resemblance to the venomous Coral Snake. This mimicry provides the non-venomous snake with a protective advantage, as predators often avoid them, mistaking them for their venomous counterparts.

Habitat Diversity:

Non-venomous snakes are incredibly adaptable creatures, thriving in a myriad of environments. From the arid deserts of the American Southwest, where species like the Gopher Snake reside, to the dense rainforests of Asia, home to the reticulated python, these snakes have evolved to suit their surroundings.

Their adaptability also extends to urban environments, where species like the common garter snake can often be found in gardens and parks, helping control pest populations.

Thermoregulation:

Being ectothermic, snakes rely on their environment to regulate their body temperature. This is crucial for their metabolic processes, digestion, and overall activity levels. To achieve the desired body temperature, non-venomous snakes engage in behaviors like basking in the sun or seeking refuge in cooler shaded areas.

Some species might even burrow into the ground to escape extreme temperatures. Rocks, logs, and other sun-exposed surfaces often serve as ideal basking spots, allowing snakes to absorb heat efficiently.

Reproductive Strategies:

The reproductive methods of non-venomous snakes can vary widely. While many are oviparous, laying eggs in concealed locations like under logs or in burrows, others are ovoviviparous, where the eggs develop and hatch inside the mother’s body, and she gives birth to live young.

The number of offspring, frequency of reproduction, and level of parental care (which is generally minimal in snakes) can differ significantly among species. For instance, the Boa Constrictor gives birth to live young, while the Ball Python lays eggs and is known to coil around them, providing warmth and protection until they hatch.

FAQ

1. How can I differentiate between a venomous and a non-venomous snake?

While there are some general characteristics that might help, such as the shape of the pupil or the presence of heat-sensing pits, it’s essential to note that these can vary by region and species. The safest approach is to avoid handling any snake if you’re unsure of its species and consult a local expert or guidebook.

2. What should I do if I find a snake in my house or garden?

Remain calm and avoid making sudden movements. If possible, isolate the snake by closing doors to the room it’s in. Contact local wildlife control or a snake expert to safely remove and relocate the snake.

3. Are non-venomous snake bites dangerous?

While non-venomous snake bites aren’t poisonous, they can still cause injury or infection. It’s essential to clean the wound thoroughly and seek medical attention if there are any signs of infection or if you’re unsure about the snake’s species.

4. How do snakes communicate with each other?

Snakes primarily use chemical signals, or pheromones, to communicate. They also rely on body language, such as coiling or hissing, to convey messages, especially during mating rituals or when feeling threatened.

5. Do snakes have a sense of hearing?

Snakes don’t have external ears, but they can sense vibrations through their jawbones, which helps them detect approaching threats or prey.

6. How often do snakes need to eat?

The frequency varies depending on the species, size, and what they eat. Some large snakes might eat once a week or even less frequently, while smaller species might need to eat more often. After consuming a large meal, some snakes can go without food for weeks or even months.

Final Thoughts

After delving into this list, I hope you’ll reconsider your initial reactions upon encountering a snake. Most of them pose no threat to humans, and even the venomous ones typically don’t attack without provocation.

Remember, when snakes strike at humans, it’s usually a defensive response, triggered by feeling endangered. If you ever come across a snake, the best course of action is to contact professional snake rescuers or your local zoo.

These experts are equipped with the knowledge and skills to manage even the most venomous species and can ensure their safe return to the wild.